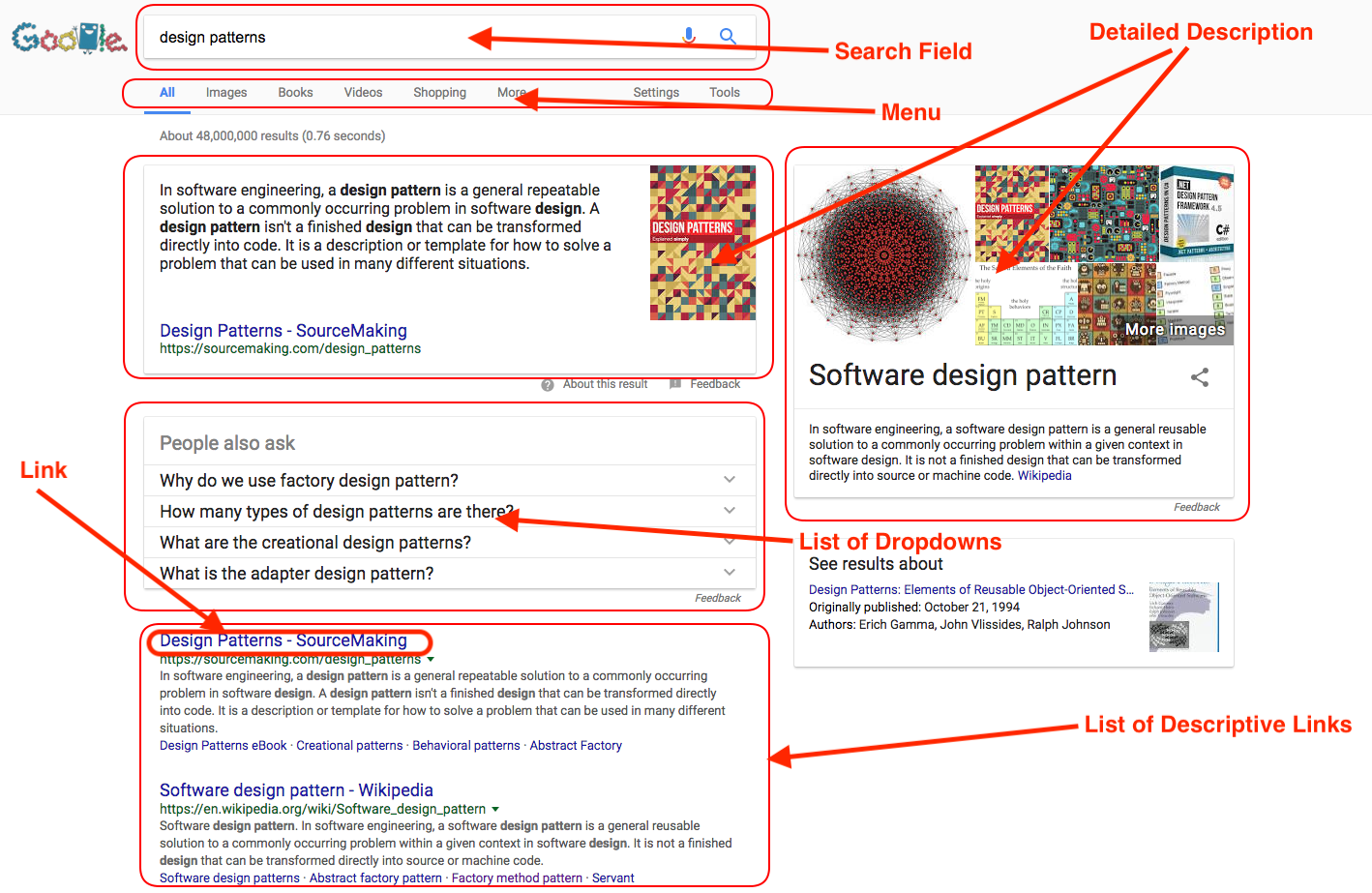

What’s design pattern

There is no such thing as “good” or “bad” design pattern. First of all the term “design pattern” was introduced to represent the problem and its optimal solution. That’s why if you don’t want to use the particular design pattern in development, test automation, etc., it doesn’t mean it’s bad, wrong or outdated. It just means that the pattern is not applicable to your problem. Otherwise if this pattern resolves similar problem to yours, it’s better to take a closer look at it.

Thus this is generally not a good idea to use the pattern only because you heard “it’s cool” from someone. Instead you need to understand its goals, problems it can solve and benefits you might get from using it.

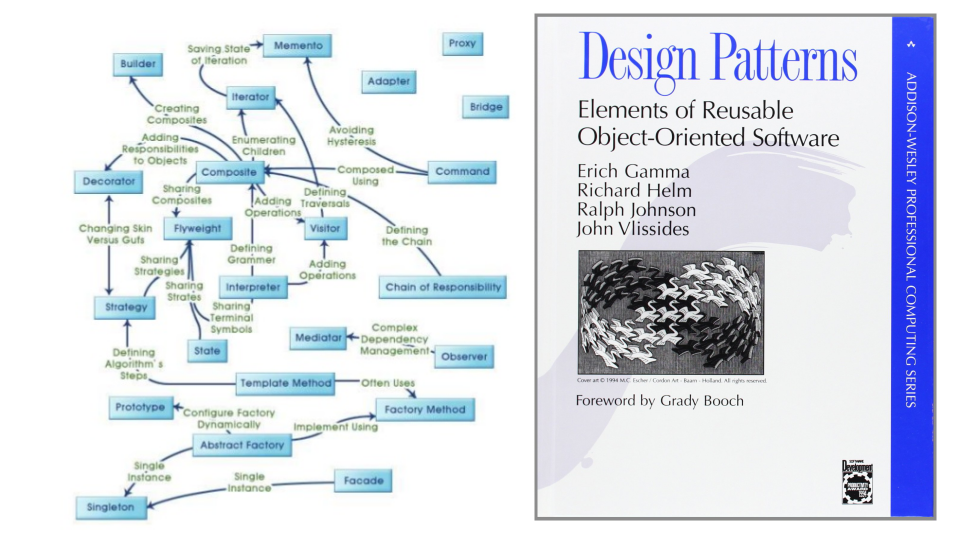

There has been always a lot of problem in designing software architecture, faced by different people. Some of them came up with the solutions to them and created the patterns. The first ones who did that and classified most of the classic design patterns were the Gang of Four. They published the book “Design Patterns”, where they showed why, when and how to use every particular known pattern in object oriented programming. Some of the patterns, described in the book, are outdated, some are missing, but the main concept is still the same - if there is a problem, there should be a solution to it.

This idea was so great, almost every industry adopted it. Software test automation was not an exception. Today we will talk ones, which are specific to testing and automation.

Why do we need patterns in our tests

The main reasons for leveraging design patterns in test automation is increasing of stability, maintainability, flexibility, reliability and clarity. All of them are important but different aspect can be reached by using different patterns.

Most of them could be assigned to some group by the problem it helps to solve:

- Structural patterns

- Data patterns

- Technical patterns

- Business involvement patterns

In the first part I’ll cover structural patterns, the next articles will cover others.

Structural Patterns

The main goal of structural patterns is to structure test code to simplify maintenance, avoid duplication and increase clarity. By doing that we will make it easier for other test engineers, not familiar with other code base, to understand and to start working with the tests right away.

Page Object

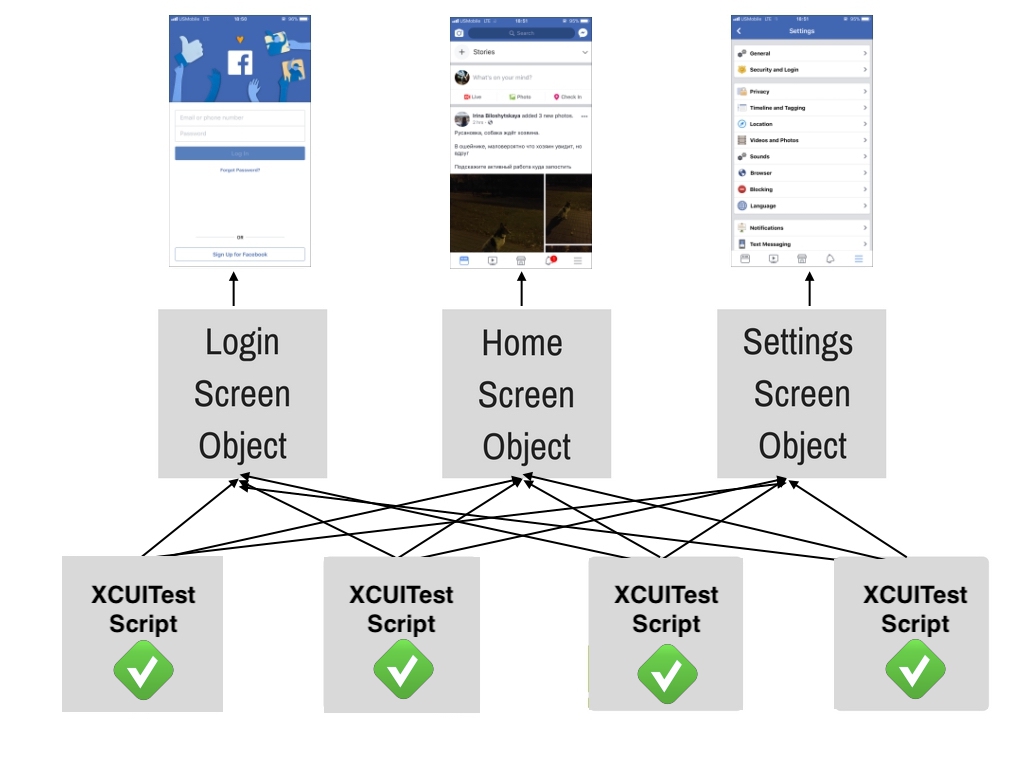

The first pattern we’ll take a look at is Page Object. Probably it’s the most famous one among test engineers. The main problem it solves is the separation of technical details (e.g. user interface elements on the page/screen) and actual test logic of UI test.

Secondly, it helps to reduce code duplication. We would like to reuse our code in different test scripts and Page Object may help us to do that. Sometimes when I add new tests to my projects I don’t have to write any extra class or function except of the test script. Because they were already written with Page Object!

And finally Page Object makes tests more readable and understandable. It shows which page is user on right now and prevents test from doing actions not related to current page.

Of course, Page Object is not a panacea. If I had small amount of tests in my project (i.e. less than 20) and did not plan to extend those, I would consider not to use it. Just because the effort to create page objects would not pay off. Each pattern may generate a great value for you project but they should not be your goal in favor of project needs.

I wrote a couple of posts on Page Object in iOS and Android testing. If you’re interested in technical details, don’t hesitate to check them out.

Fluent / Chain of Invocations

The second pattern we were going to talk about is Chain of Invocations. It’s usually being used along with Page Object, so most of you might be familiar with it too. The problem it resolves is helping test developer to determine if she can use the object or she should switch to other one. For example, user is on the login page and he’s pressing some button. By writing code in old fashion we wouldn’t be sure if he’s still on the login page or already on the home page.

And now just imagine if you had 50 similar methods in your test. You cannot be sure if you can invoke them right away, or they depend on some order, or even they can not be invoked after one of them was executed. For example, can I click on hint dialog if I haven’t entered any character into input field? Probably not, because at the very moment, it doesn’t exist yet!

public void loginToAccountShouldWork() {

homePage.typeLogin(user.login);

homePage.typePassword(user.password);

homePage.tapSignInButton();

assertThat(homePage.isSignedIn(user));

}

public void loginToAccountShouldWork() {

homePage

.typeLogin(user.login)

.typePassword(user.password)

.tapSignInButton();

assertThat(homePage.isSignedIn(user));

}

This pattern is important in case you’re trying to scale your test automation framework. Large amount of pages, elements and methods available for usage may create a confusion, especially for someone not really familiar with your domain. But by implementing Fluent Invocations modern IDE will give you a hint every time you’ll try to invoke some method on the object by autocompletion feature.

Usually if you want to interrupt method chain, all you have to do is to assign the return value (e.g. string, number etc.) to some variable. This way you’d show that this is the end of the sequence of invocations. At this point developer should stop and think about next method to be invoked in test script before doing that.

Chain of Invocations is easy to implement. All you have to do is to return the value in every method of Page Object. This might be this, some value or any other object, for example next Page Object after method invocation (transition to other page).

This pattern doesn’t help to reduce code a lot (that’s not its mission thought), but it allows you to not repeat yourself by putting the object again and again before invoking its methods. Also IMO it makes code a little bit prettier.

Page Factory

Page Factory is an extension to Page Object pattern. It helps to encapsulate page’s attributes and methods even more by providing FindBy annotations.

public class LoginPage extends BasePage {

private static final By USERNAME_FIELD =

By.id("usernameField");

private static final By PASSWORD_FIELD =

By.id("passwordField");

private static final By LOGIN_BUTTON =

By.id("loginButton");

public LoginPage(WebDriver driver) {

super(driver);

}

public HomePage loginAs(User user) {

driver.findElement(USERNAME_FIELD)

.sendKeys(user.username);

driver.findElement(PASSWORD_FIELD)

.sendKeys(user.password);

driver.findElement(LOGIN_BUTTON)

.click();

return new HomePage(driver);

}

}

public class LoginPage extends BasePage {

@FindBy

private WebElement usernameField;

@FindBy

private WebElement passwordField;

@FindBy

private WebElement loginButton;

public LoginPage(WebDriver driver) {

super(driver);

PageFactory.initElements(driver, this);

}

public HomePage loginAs(User user) {

usernameField.sendKeys(user.username);

passwordField.sendKeys(user.password);

loginButton.click();

return new HomePage(driver);

}

}

Pay attentions to PageFactory#initElements invocation. This static helper initializes all fields with FindBy annotations on the page, which will be found on it on each call. The main advantage is the fact that now we work directly with fields, buttons, windows etc. and do not worry about low level driver’s interactions exactly the same way our app users do.

Composition of Page Elements

Any web, desktop or mobile application consists of repeatable elements, and logic of their usage should be implemented again and again in our tests. For instance, every menu has list of links, every table has rows and columns, every form has input fields. In real life when we work with those elements we do not separate those components from the main element consisting them.

Thanks to Composition we could implement some elements once and reuse them every time we need them. Thus it helps to avoid code duplication by composing different web elements into widgets (high-level elements), like tables, menus, forms. This significantly reduces costs of extending and scaling of test automation framework when, for example new Page Objects needs to be created.

Loadable Component

This pattern is used by most of the developers who works with user interface tests. The thing is, when test makes the transition from one page to another, it doesn’t know if the targeted page was loaded completely. Obviously, either regular sleep or not waiting at all is not a solution here. So how do we solve this problem? Usually test engineers create explicit wait in constructor of the page class or in its ancestor and override if it’s needed.

public class HomePage extends BasPage {

@FindBy(id = "someId")

private WebElement element;

public HomePage(WebDriver driver) {

super(driver);

PageFactory.initElements(driver, this);

waitForElement(element);

}

}

Again, there is not strict rule how to do this wait. Personally I like to move this waiting to BasePage and override abstract method for waiting particular element. How to do that in your case, completely up to you. But before implementing such complicated logic you need to be sure that your app page transition could cause you some problem. Otherwise just usual implicit wait might be enough. If you’re interested in implementation of explicit waits in your UI mobile tests and do not know where to start, I recommend to read my post about explicit waits in Android or iOS.

Strategy

Strategy pattern is used whenever we want to have more than one implementations of the same action/sequence of actions, which is done differently. Depending on the context we could choose the implementation.

The easiest example is user registration. You might want to have two different implementations of this particular action. The first one would be the actual flow of transitions through the pages for successful user registration. The other one would be short API call which is invoked when new user is needed for the test.

interface UserRegistrationStrategy {

User register();

}

class WebUserRegistrationStrategy

implements UserRegistrationStrategy {

@Override

public User register() {

String username = UserRegistry.getUsername();

String password = PasswordGenerator.generatePassword();

SignInPage.open()

.pressSignUpButton()

.enterUsername(username)

.enterPassword(password)

.clickRegisterButton();

return new User(username, password);

}

}

class ApiUserRegistrationStrategy

implements UserRegistrationStrategy {

@Override

public User register() {

User user = new User(UserRegistry.getNewUsername(), PasswordGenerator.generatePassword());

put("api/user").withBody(user.toJson());

return user;

}

}

You may not want to invoke “long” registration every time in your tests. But sometimes you’ll need it, for example when you validate actual registration through the web. And vice versa, we want new user creation for test needs to be fast and reliable. That’s why REST registration would be suitable here.

Strategy helps making our test automation framework more flexible and easier in maintenance by using separation of concepts. Again you need to be careful and not implement it in situations when you can do fine without it.

That’s it for Structural Patterns. I’ll make overview of other pattern types in the next articles:

Comments