I already wrote about using Structural and Data Patterns in your automated tests before. That’s why if you’d like to learn more, you should check those posts out. In today’s last part of the series we’ll be talking about Technical and Business Involvement patterns.

Technical Patterns

The main goal of Technical Patterns is to encapsulate technical details from test logic, providing extra low-level control over them.

Decorator

Decorator is a very well-known pattern, since it was mentioned in the GoF list and discussed in many other programming books and articles. The example of this one is simple. Let’s imagine you’re working with any driver implementation (e.g. WebDriver) and are willing to add an extra functionality to it, like logging or caching. But in the same time you don’t wanna reveal that additional functionality to your actual tests, leaving test logic the same as it was before. That’s where you want to use Decorator.

Decorator helps to implement so called “Cabbage principle”, when you are able to wrap one driver implementation into another, in the way cabbage leaves are formed. Your tests won’t be aware of that extra layer since they work with the same interface as before.

For instance, you want to log every click on some element in your tests. All you need to do is to decorate your initial WebDriver object, by wrapping it into the EventFiringWebDriver and registering new listener, while your tests don’t have to be changed at all:

new EventFiringWebDriver(driver)

.register(new AbstractWebDriverEventListener() {

@Override

public void afterClickOn(WebElement element,

WebDriver driver) {

LOG.log(Level.INFO, "Click on element "

+ element.getTagName());

}

});

To get rid of this kind of wrapping in the test logic completely, one could leverage something like Factory Pattern, when user can get the browser/driver simply requesting it from the Factory. Also using the Browser Pool might be not a bad idea too.

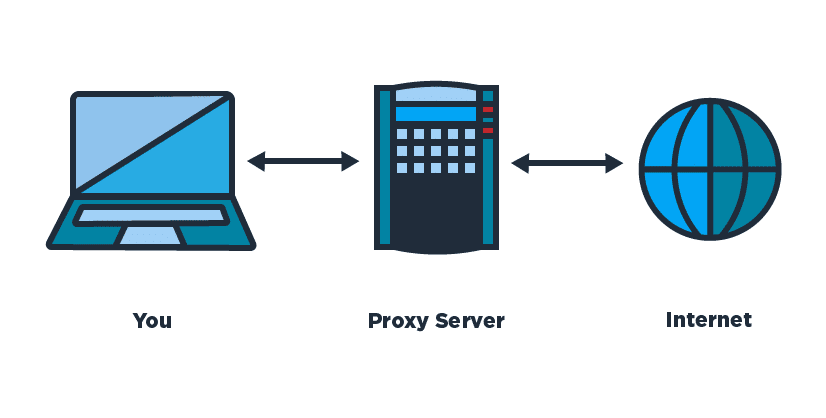

Proxy

Proxy is the pattern that allows to intervene into the process running between you and another user, introducing new logic in-between without affecting either of the sides.

This pattern might be useful when you, for example, want to add logging, to enable or to disable something, to have control over some additional recourses etc. The most popular method of using it in tests is to set up the HTTP proxy. It allows to dynamically enable and disable host blacklists, excluding or stubbing the third-party sites like Facebook or Twitter in your tests. Sometimes it’s the only way you can check some exceptional scenarios for the external services like those ones.

Another two examples I could come up with are caching of nonfunctional assets (like images or CSS), which do not affect the functionality of the app, and collecting http-traffic for further analysis while running the tests (by analysis I mean verifying if some images were missing or if any recourses took a lot of time to load etc).

Use HTTP Proxy for tests to:

- Blacklist external resources (Facebook, Twitter, Ads etc)

- Cache images and other nonfunctional assets

- Collect HTTP traffic for analysis (loading time, 404 errors, redirects etc)

- Speed up page loading

Business Involvement Patterns

The last group of patterns I was going to review is Business Involvement Patterns. The main goal of these patterns is to bring Product Owners, Business Analytics and other people, responsible for requirements, as close to test automation as possible. This way its benefits might become crystal clear to them and they would get involved into it as much as we are. It’s the perfect scenario for all the members of the team, isn’t it?

Keyword Driven Testing

To make the latter possible we could use the popular pattern, which allows to distance tests from the code and helps to make it possible to write them in human-readable language, understood to regular person.

Keyword Driven Tests are written using keywords - domain commands, clear to everyone in the team. Hence they might contain some data, they should be implemented by people, who’s familiar with the technical details and are able to design them in code. But in the same time the framework should allow anyone to write the tests - it might be manager, business analytic or test engineer without any coding experience.

*** Settings ***

Documentation A test suite with a single test for valid

login.

This test has a workflow that is created

using keywords in the imported resource

file.

Resource resource.txt

*** Test Cases ***

Valid login

[Set Up] Open Browser

Open Login Page

Input Username someUser

Input Password somePassword

Submit Credentials

Welcome Page should be Opened

[Teardown] Close Browser

In the example above, you can see how this pattern is implemented with the help of Robot Framework. There are lots of free and paid frameworks out there, which help to adopt KDT approach and make Business’s life easier.

The main idea behind this is that there is finite number of operations in any app. This means that if all of them are implemented as keywords, we are able to build infinite number of test scenarios by combining them in one or another way. Doing this you could provide the working tool to someone who wants to be involved into the building of the automation on the project.

This pattern faced a lot of critics from people who implemented it in their automation but weren’t able to involve anyone from business side into writing the tests. That’s why before implementing Key Driven Testing on your project you should discuss its usage with all the stakeholders. Otherwise it might be overhead to build something complex like this without business awareness and support.

Behavior Specification

The same is true for the next pattern we’re going to discuss - Behavior Specification. It suggests to transform the writing of the tests into defining of the expected behavior. This way the feature can be described in the form of behavior scenarios. Here is the simple example of this pattern:

Feature: Addition

In order to avoid silly mistakes

As a math idiot

I want to be told the sum of two numbers

Scenario: Add two numbers

Given I entered 50 into the calculator

And I entered 70 into the calculator

When I pressed Add button

Then The result should be 12 on the screen

The scenario describes simple workflow of addition of two numbers using calculator buttons and verification of the result on its screen. This test is not a “test” in a common sense, it’s more a behavior specification. It’s easy to read and can be understood by anyone. But again, this pattern will be super useful only if the business wants to be involved in the testing process (e.g. by creating the acceptance criteria based on those specs and tracking the results of tests).

If the business on your project is not ready for this kind of approach, you don’t have a problem which needs the given solution, and by implementing it you’d create another unnecessary layer of abstraction above your test logic.

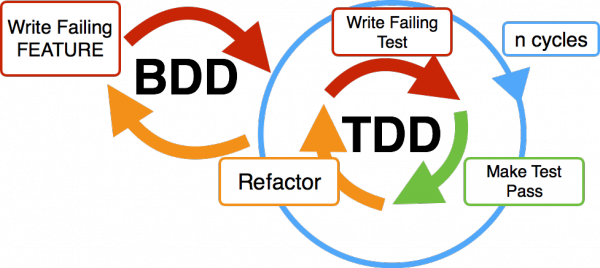

Behavior Driven Development

Usually Behavior Specification is used along with concept of Behavior Driven Development, which is saying that:

- at first we need to describe the behavior of functionality as a spec

- next we want to write a test for that

- then we need to implement that functionality

- verify that test passes

- verify that behavior scenario passes

As a result we’ll get working low-level tests and comprehensive high-level scenarios, making developers and business happy, right? But I’m afraid its not that simple. It would be complete waste of time if this approach is used by engineers (technical people) exclusively without involving any business to writing scenarios.

Steps

The last for today pattern’s idea might be pretty interesting regardless what approach you’re using: Behavior Driven, Keyword Driven Development or Behavior Specification. When we’re talking about logic scenarios, we think about them as if they consist of steps. But when you implement them in your code, these steps often get lost among all the technical details, data manipulations and other things we’re doing in our tests. It would be great if we could isolate those steps from other code showing what this particular test does and easing the hurdle of its maintenance. Steps pattern will help us to do that!

Your test steps might be divided into groups by functionality and gathered into the special classes or methods. If you don’t have the step you need in your test, you can simply create one. You can use the Steps Pattern either with some technical framework (e.g. Page Object) or without any. It doesn’t matter as long as you divide your logic into the Steps:

public void bookShouldBeSearchedByName() {

loginToBookStore("u", "pass");

openBookSearchPage();

enterSearchCriteria("name", "selenium");

assertFalse(isEmptySearchResult());

openBookDetailsByIndex(1);

assertEquals("Selenium 1.0 Testing Tools", getBookTitle());

assertEquals("David Burns", getBookAuthor());

}

The Steps example above can be easily transformed to a Test Scenario:

Steps:

1. Login to book store as user 'u' and password 'pass'

2. Open search books pages

3. Try to search by word 'selenium'

4. Results should not be empty

5. Open the first found book details

Expected results:

1. Book title is 'Selenium 1.0 Testing Tools'

2. Author is 'David Burns'

Writing test scenarios in this way may help to avoid using of any extra Test Case Management system, since all of the Test Steps, either automated or manual ones, are stored in one place, which is your framework. As a bonus now you can easily track, how many steps are automated, how many of them are broken, who was responsible for their creation etc.

It’s pretty simple to write a great test. The other thing is to write dozens of them while the functionality of your app is scaling, the number of people on your project responsible for the tests is growing, without losing the speed of development and avoiding the time wasting on supporting of those tests etc. The latter can be done leveraging the Design Patterns discussed in the Patterns series in this blog. If you know how and when to use them, your tests will be faster, more effective, more scalable and more reliable.

Comments